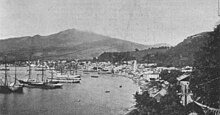

Wrecks of Saint-Pierre harbor

The eruption of Mount Pelée on May 8, 1902 generated a pyroclastic flows, also known as nuées ardentes (Fr: burning clouds) cloud famous for having destroyed in a few minutes the town of Saint-Pierre, Martinique, at the time the administrative and economic capital of Martinique.

During this eruption, many boats were in the bay of Saint-Pierre. Like the city, they were destroyed in an instant. The majority caught fire and destroyed their bodies and property[1],[2], [3], [4]

The fishermen knew the locations of some of the wrecks. They sometimes blocked their nets and were areas rich in fish. With the advent of scuba diving in the 1970s, wreck hunters set out in search of sunken boats. Michel Météry is known to be the main inventor of most of these wrecks. Jacques Cousteau, Albert Falco and Dominique Serafini on the Calypso were also among those who searched for them.

These boats are now very attractive diving sites for divers who live or come to Martinique. All local diving clubs organize many trips to these sites. The Roraima, by its size and the quality of conservation, is the most emblematic of these wrecks. The Tamaya is the most mysterious because it is too deep for air diving. The Grappler with his "treasure" is still sought after...

To preserve these cultural and heritage assets of Martinique, in 2012 the city of Saint-Pierre and the French state took the decision to protect the wrecks resting in the harbor of Saint-Pierre[5]

The Frank-A.-Perret Museum of the City of Saint-Pierre recently launched a podcast in French dedicated to the wrecks located in the harbor Saint-Pierre. This podcast highlights various speakers, presented in alphabetical order: Mathurin Cadenet, originally from Saint-Pierre (nicknamed "Pierrotin"); Daniel Eustache, also Pierrotin and fisherman; Jean-Sébastien France, diver and president of the Association for Research and Valorization of the Archaeological Heritage of Martinique (ARVPAM); and Michel Météry, diver and discoverer of the wrecks in the harbor of Saint-Pierre.

Archaeological research[edit]

The harbor of Saint-Pierre is now recognized for its significant archaeological value. Due to its historic status as the capital of Martinique and the large number of boats that it permanently welcomed, the harbor preserves precious traces of the past under its waters.

The University of the West Indies has organized several excavation campaigns in collaboration with the Naval Archeology Research Group (GRAN)[6] and the Laboratory of Medieval and Modern Archeology in the Mediterranean (LA3M)[7]. The Department of Underwater and Underwater Archaeological Research (DRASSM)[8] of the Ministry of Culture also carried out research to carry out prospecting, inventory and geophysical studies of the site.

During its various campaigns, the GRAN established a detailed list of fragments[9] and wrecks[10] in the bay of Saint-Pierre as well as throughout Martinique. In 2023, the European Union launched the ecoRoute program in Martinique, focused on "The northern route around the wrecks of Saint-Pierre". This program is supported by the Archaeological Association Small Antilles Archeology (AAPA)[11].

Amélie / Raisinier[edit]

A 48 meter long steel sailboat suffered a leak in its hull while it was at anchor in the harbor of Saint-Pierre. The crew battled the damage for two days, before the boat was towed to Turin Cove, where it finally sank. During its research, GRAN[6] discovered various fragments, including the remains of an iron sailboat, badly damaged by the sea, near Raisinier beach[12],[13]

The wreck lies at a depth of 12 meters.

Biscaye (Ex Gabrielle)[edit]

The three-masted schooner-rigged sailing ship, built of wood with a hull lined with copper plates, was built in Bilbao in 1878. It measured 32 meters long by 7 meters wide.

Armed by a company from Bayonne, where its home port was located, this sailboat provided, under the command of Captain Jules Trevilly/Trivily, the connection between Martinique and Saint Pierre and Miquelon for the transport of cod. Departing from Bordeaux on February 17, 1902, it reached Saint Pierre and Miquelon before arriving in Saint-Pierre in Martinique on May 6, with a cargo of 700 barrels of cod. On May 8, 1902, he was at anchor in the bay of Saint-Pierre, less than 200 meters from the shore, facing Place Bertin. Archaeological excavations of the wreck revealed the presence of cod barrels.

Due to its construction, it probably caught fire quickly, unless the small tidal wave following the fiery cloud caused it to capsize and sink.

The wreck was rediscovered in the 1970s and was initially misidentified as that of the Gabrielle. The wreck measured 32 meters long, while the Gabrielle measured only 23 meters. Although the Gabrielle was at anchor on May 8, she was not found.

The wreck which was the subject of the 1994 dedicated research by GRAN[14]. During their underwater diving, the following report was made[15]:

The wreck of a ship, characterized by a copper-lined hull, is located practically in the axis of the Saint-Pierre pontoon. Oriented east-west, with the front facing east, it rests on a slope: the front is 29 meters deep and the rear is 39 meters deep. The hull is approximately 40 meters long. The ship is lying on its port side, clearly revealing on starboard the rhythm of the membranes and the remains of the planking with the lining.

The metal rudder[16], relatively well preserved, emerges one meter from the sand. It has a thickness of 24 cm at the top and a retained width of 60 cm. The notch intended to receive the upper hinge measures 17 cm high and is located 8 cm below the preserved top of the rudder. The lining measures 7 cm thick, the membranes 17 cm thick and 30 cm wide, and the planking 10 cm wide.

An anchor approximately 2 meters long lies to the northeast of the front of the wreck, approximately 20 meters away, oriented east-west. It is likely that it belongs to the wreck.

Michel Météry had initially named this wreck Gabrielle, because of its position seeming to correspond to that of the Gabrielle anchorage according to Lacroix's book. However, Bureau Veritas records indicate that the Gabrielle, which sank in Saint-Pierre from the Knight armament, measured 23 meters long, while this wreck measures 31. We can therefore conclude that this wreck is not that of Gabrielle.

Three elements lead to the identification of this wreck as that of the ship Biscay:

- The length of the ship.

- The type of doubling.

- The cargo of fish.

The data is summarized below:

- Length preserved between 29.10 and 31.20 meters.

- Lining and doweling in yellow copper alloy.

- During the 1994 survey, a cargo of barrels containing skeletons of gadids (fish of the cod family) was discovered in the bottom of the ship.

Among the ships sunk at Saint-Pierre, only the Biscay has a length corresponding to these measurements. We can estimate the length of the Sacro Cuore and the Teresa lo Vico from that of North America, since their tonnages are very close. The type of double used for the Biscay also seems to correspond to that of the wreck. No other ship being reported as loaded with fish, we can affirm that the wreck is indeed that of the Biscay of Bordeaux.

Clémentina[edit]

The wreck is a hull bottom approximately 20 meters long, belonging to a locally built coaster[17]. This wreck was the victim of several lootings or attempted lootings, which led the Directorate of Antiquities to file several complaints with the gendarmerie. Some objects were saved thanks to these interventions. Not listed on Hydrographic Service documents, it is nevertheless well known to local divers.

Characteristics of the wreck

- Hull: Wooden, lined with copper.

- Position: The hull rests on the keel, on a slope covered with mud. The rear of the boat rests at a depth of 50 meters (49 meters on the mud at the foot of the rudder) and the front is 40 meters away, giving the boat's axis an angle of 30° to the horizontal (slope of 56%). This axis is oriented at 116°.

- Dimensions: Total length of the hull without the rudder: 20.6 meters. Retained width: 6.80 meters.

Saffron details

- Material: Metallic, still in place and very visible, protrudes 90 cm from the vase.

- Dimensions: Width of 75 cm at the top, 87 cm at the level of the vase. Thickness of 17 cm.

- Fixing: The upper rudder fixing hinge is still movable on its axis and still carries its fixing rivets with a diameter of 2 cm. The wooden parts have disappeared, leaving only the metal frames.

- Rudder: The preserved part of the rudder, stern post (31 cm) and counter post (21 cm), does not show any trace of a propeller cage, indicating that it was a sailboat.

Structure and materials

- Background: The shape is preserved by the copper plates of the doubling, forming a hollow mold of the hull. On the two front levels, the wood remains visible.

- Sampling of the frames: Bordered 6 to 7 cm thick, membrane 18 x 18 cm, lining approximately 6 cm thick.

- Dubbing plates: The front plates are twisted, probably as a result of an impact. The vessel's modest size suggests a barge or coaster.

Analysis and discoveries

- Wood species: Analyzes revealed the use of three different species: spruce for the lining, pine for the frames, birch for the planking. However, it was not possible to determine the exact species or origin of the wood, which may come from Europe or America.

- Objects recovered: A port lantern cleared by a clandestine survey was saved and placed in storage at the Directorate of Antiquities.

The wreck of 'Clementina' remains a subject of significant archaeological interest, providing valuable information on local shipbuilding and maritime practices of the time.

The wreck lies 20 meters deep.

Dalhia / YMS 82[edit]

Diamant[edit]

Barge du Diamant[edit]

Fause Thérésa[edit]

Grappler[edit]

Nord-America[edit]

Roraima[edit]

Tamaya[edit]

Theresa Lo Vigo[edit]

Yacht italien[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

External link[edit]

- Book : La Catastrophe de la Martinique (Hess)[18]

- The excavation campaigns of Groupe de Recherche en Archéologie Naval (GRAN)[19]

- Sites list by archéologiques sous-marins de la Martinique du GRAN[20]

- Notice archéologique - Archéologie de la France - Informations (ADLFI). : Au large de Saint-Pierre – Le dépotoir portuaire de la rade[21]

- The Frank-A.-Perret Museum of the City of Saint-Pierre recently launched a podcast in French dedicated to the wrecks located in the harbor Saint-Pierre. This podcast highlights various speakers, presented in alphabetical order: Mathurin Cadenet, originally from Saint-Pierre (nicknamed "Pierrotin"); Daniel Eustache, also Pierrotin and fisherman; Jean-Sébastien France, diver and president of the Association for Research and Valorization of the Archaeological Heritage of Martinique (ARVPAM); and Michel Météry, diver and discoverer of the wrecks in the harbor of Saint-Pierre.

References[edit]

- ^ Météry, Michel; Falco, Albert (2002). Tamaya: les épaves de Saint-Pierre. Paris: Inst. Océanographique. ISBN 978-2-903581-30-5.

- ^ Denhez, Frédéric (1997). Les épaves du volcan : Saint-Pierre de la Martinique. GLENAT. ISBN 9782723424622.

- ^ SERAFINI, Dominique (2015). Saint-Pierre l'Escale Infernale: TragédieMaritime - Éruption du Mont Pelé - Martinique 1902. S.QuemereImbert.

- ^ Ramadier, Sylvie (May 2005). "Le 8 mai 1902 saint pierre est enseveli sous la lave".

- ^ "Zones de protections des épaves historiques de Saint-Pierre" (administrative document). 19 May 2022.

- ^ a b "GRAN".

- ^ "la3m".

- ^ "DRASSM".

- ^ "GRAM : Site List".

- ^ "GRAM : shipwreck list".

- ^ "AAPA - projet eco route".

- ^ "divingaway".

- ^ "GRAN inventory ID : FR/M/3/A/027".

- ^ Guillaume, Marc (1994). "Saint-Pierre - Sondages sous-marins". Archéologie de la France – Informations (AdlFI).

- ^ "GRAN inventory ID : FR/M/1/A/015".

- ^ "GRAN inventory ID : FR/M/3/A/016"".

- ^ "GRAN inventory ID : FR/M/1/A/006"".

- ^ HESS, JEAN (1902). LA CATASTROPHE DE LA MARTINIQUE — NOTES D'UNREPORTER (in French). Librairie Charpentier et Fasquelle.

- ^ "GRAN - Reseach campagne".

- ^ "GRAN : Site list".

- ^ Serra, Laurence; Billaud, Yves (September 2019). "Fouilles Saint pierre". Adlfi. Archéologie de la France - Informations. Une Revue Gallia.